Candies, Pens, Pads (with or without wings)?

Trekking the Annapurna Circuit in Nepal back in 2007, I often encountered children from the nearby villages yelling “pens, pens” when we crossed paths. I thought, well that’s better than “sweets, sweets” which was a common refrain while backpacking through Latin America and Southeast Asia. I would read in guidebooks that the en vogue recommendation of that time was to give children useful tools such as pens for schoolwork rather than the dental bulldozer of candy. I never gave the recommendation or my observation much thought beyond my default position of never giving out handouts. I thought it unethical to have children assume that begging was a dignified means to an end or that foreigners were a walking atm or a solution to their daily needs. So has my position changed?

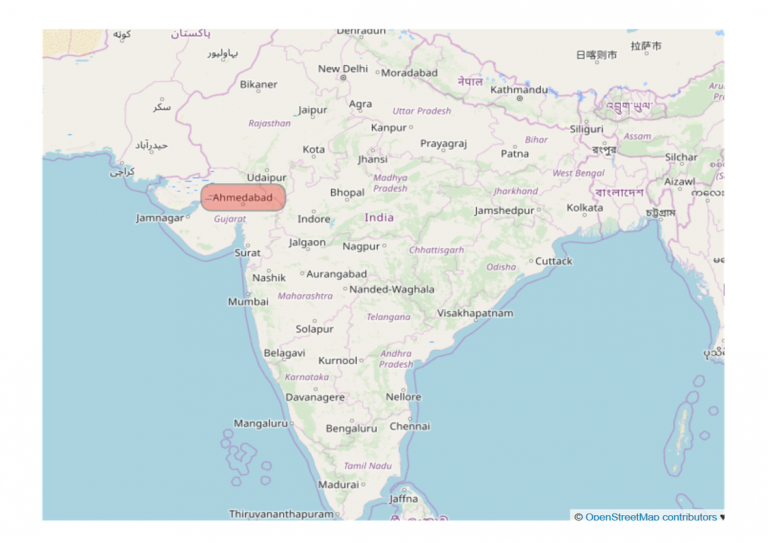

Backpacking through Myanmar and India, I was shocked by the signs outside and inside religious temples. One venerable temple in Yangon, Myanmar posted a sign inside that prohibited women from circumambulating and touching a golden Buddha statue. I never thought of Buddhists as segregating men and women so was surprised and pissed off that I couldn’t continue with my tourist pursuits. A temple in Ahmedabad, Gujarat State, India posted a sign outside the temple that prohibited “menstruating women” from entering the temple. My only thought was “wtf”. What does my normal, biological, menstrual cycle have to do with anything sacrilegious?.

Backpacking through Myanmar and India, I was shocked by the signs outside and inside religious temples. One venerable temple in Yangon, Myanmar posted a sign inside that prohibited women from circumambulating and touching a golden Buddha statue. I never thought of Buddhists as segregating men and women so was surprised and pissed off that I couldn’t continue with my tourist pursuits. A temple in Ahmedabad, Gujarat State, India posted a sign outside the temple that prohibited “menstruating women” from entering the temple. My only thought was “wtf”. What does my normal, biological, menstrual cycle have to do with anything sacrilegious?.

You’re probably thinking what does this have to do with handouts of candy or pens? Bear with me. Honestly, once I returned home, I didn’t think or research more about the origins of the cultural taboos that led to those signs. I mainly thought that some cultures are so backwards when it comes to women. Maybe it’s a function of more time to reflect, but those signs have been gnawing at me subconsciously and I finally want to understand.

So why are women and menstruating women prohibited from those religious sites?

I have now discovered that the three Abrahamic faiths (Judaism, Christianity and Islam) as well as Hinduism and Buddhism have taboos surrounding menstruation. Hinduism considers menstruating women as polluted and prohibits them from cooking, sharing utensils or entering temples and participating in religious ceremonies. Though Buddhism traditionally views menstruation as a natural biological excretion, Hindu beliefs have influenced aspects of Buddhist culture and some Buddhists prohibit women from meditating or taking part in ceremonies. The temple in Yangon, Myanmar is the only Buddhist temple – I have been to countless Buddhist temples around the world- where I have encountered a restriction on women. Many of you, and myself included, may not realize that Christianity was/is hardly any less judgmental. The Book of Leviticus in the Old Testament states that menstruating women are unclean and anything she touches is polluted. Leviticus as part of the Torah also instructs Judaism, and Orthodox Jewish women are expected to avoid physical contact with family members and to purify themselves in a ritual bath at the conclusion of their period. Contemporary discourse surrounding the all-male priesthood and the leadership of the Catholic Church fails to mention that early Christian women were often barred from entering a church during menstruation and prohibited from leadership roles due to the thinking of menstrual blood as pollution. Even now, some Orthodox Christian Churches prohibit menstruating women from receiving communion. Islam is not fundamentally different, treating menstruation as impure. Menstruating women are prohibited from entering a mosque and prohibited from praying or fasting during Ramadan. My menstruating Muslim colleagues in Indonesia seemed to enjoy their lunches in almost empty cafeterias during Ramadan, but they weren’t given a choice to fast or not.

I have now discovered that the three Abrahamic faiths (Judaism, Christianity and Islam) as well as Hinduism and Buddhism have taboos surrounding menstruation. Hinduism considers menstruating women as polluted and prohibits them from cooking, sharing utensils or entering temples and participating in religious ceremonies. Though Buddhism traditionally views menstruation as a natural biological excretion, Hindu beliefs have influenced aspects of Buddhist culture and some Buddhists prohibit women from meditating or taking part in ceremonies. The temple in Yangon, Myanmar is the only Buddhist temple – I have been to countless Buddhist temples around the world- where I have encountered a restriction on women. Many of you, and myself included, may not realize that Christianity was/is hardly any less judgmental. The Book of Leviticus in the Old Testament states that menstruating women are unclean and anything she touches is polluted. Leviticus as part of the Torah also instructs Judaism, and Orthodox Jewish women are expected to avoid physical contact with family members and to purify themselves in a ritual bath at the conclusion of their period. Contemporary discourse surrounding the all-male priesthood and the leadership of the Catholic Church fails to mention that early Christian women were often barred from entering a church during menstruation and prohibited from leadership roles due to the thinking of menstrual blood as pollution. Even now, some Orthodox Christian Churches prohibit menstruating women from receiving communion. Islam is not fundamentally different, treating menstruation as impure. Menstruating women are prohibited from entering a mosque and prohibited from praying or fasting during Ramadan. My menstruating Muslim colleagues in Indonesia seemed to enjoy their lunches in almost empty cafeterias during Ramadan, but they weren’t given a choice to fast or not.

Women are marginalized not only during their periods but also because they are the sex that menstruates, and these religious and cultural taboos have permeated the wider society. In present day Nepal, menstruating women in rural areas are relegated to a hut outside of the family home to prevent “pollution” of shared space. Their menstruating neighbors in India are not permitted to enter the kitchen or cook meals. In Uganda, some tribes prohibit menstruating females from drinking milk from cows due to the belief that this will contaminate the herd. If others see someone’s menstrual cloth, the owner of the cloth will be cursed in Tanzania. Myths such as this perpetuate secrecy on the topic of menstruation. Strangely, despite the belief that menstruation is impure, many cultures prohibit women from bathing during their periods most likely due to bathing facilities being shared. According to a UNESCO study, one in ten girls in Africa misses school during her period because of lack of access to sanitation facilities. This often leads to higher drop out rates among girls. Add to that fact the statistic that 88% of menstruating age females globally lack access to menstrual pads or tampons. Menstruation itself is not only a stigma, but women are marginalized from fully participating in the wider society due to myths.

So what is the implication for a traveler wandering through parts of the world where menstruation is taboo and sanitary products are not available? Instead of offering the occasional candy, pen or loose change to whoever beckons, why not pass out packs of pads? They cost four or so dollars for a pack of twenty in the US and whether they have wings, are extra-long or for nighttime heavy flow, those packs are compressible and weigh little. They could provide physical comfort and psychological salve to a young teenager bewildered by the biological phenomenon or an overworked mother without the means or access to products we travelers take for granted in our home countries. I specifically mention pads opposed to tampons because tampons are penetrative and some cultures may oppose its use, especially for an unmarried female. I’m under no delusion that handing out pads will change every woman’s life, but maybe the days of comfort and psychological reprieve will give some women an opportunity to continue their education, start a wider cultural dialogue or at the minimum, normalize and give women a tool to manage a natural biological occurrence. Infrastructure such as access to water and public toilets are absolutely necessary and unfortunately they depend on long-term political decisions and the respective countries’ resources. Challenging and overturning religious taboos concerning menstruation and women as a whole are necessary, but how is that dialogue initiated in cultures where women are politically, socially and financially marginalized? With sanitary pads, the individual woman controls its use. Without the need to worry about menstrual blood staining skirts or using less than user-friendly menstrual cloths, the girls and women may be better able to actively live in their bodies and within the wider society. Carry some pads on your next trip!